Review by Stephen Amidon, Sunday Times, 20th June 1993.

Hemingway biographies should come with public health warnings, cautioning young writers that any attempt to imitate his career may seriously damage their well-being. Who knows how many ambitious boys, smitten by Hemingway’s near-perfect prose and expansive lifestyle, have drowned, suffered concussion, been detained in foreign trouble spots or wound up as members of AA in an effort to live up to the novelist’s legend? Even as formidable a writer as Raymond Carver once admitted that his own drinking problems stemmed, in part, from a wayward desire to mimic the great man’s epic whisky consumption.

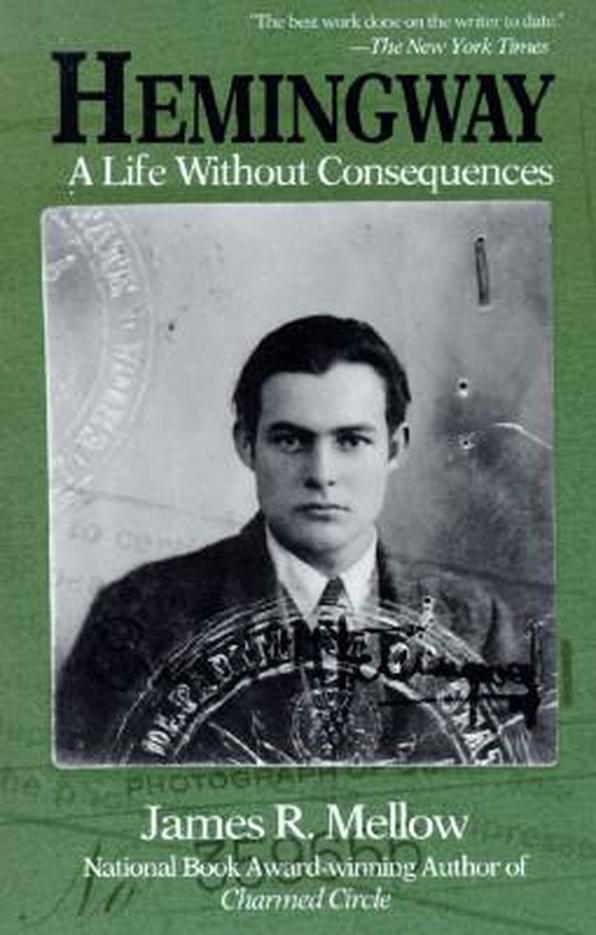

James R Mellow’s fine, assiduous biography serves as a welcome tonic for this syndrome, showing how this swaggering persona was as much the novelist’s creation as his characters Nick Adams or Frederic Henry. Hemingway biographers generally fall into two camps those, such as Carlos Baker, who see him as the embodiment of rough masculine creativity, and those, such as Jeffrey Myers, who see him as a blustering, overrated fake.

It is to Mellow’s credit that he avoids joining either cause, writing instead an even-tempered assessment of the man who, for better or worse, has come to be an archetype of what it means to be a novelist.

A Life Without Consequences is the third instalment of Mellow’s study of the American literary expatriates who congregated in Paris in the 1920s, the first two focusing on Gertrude Stein and F Scott Fitzgerald. It is this period that constitutes the meat of the book. Hemingway’s affluent, easy-going Midwestern childhood is treated as little more than a time of growing restlessness, culminating in his decision to join the Red Cross ambulance corps during the latter days of the first world war, and leading to his famous wounding and subsequent love affair with a nurse on the Italian front. He returned to America for a short spell as a journalist, but the exile bug had bitten. He was 22 when he returned to Europe with his first wife, Hadley.

It wasn’t long before his good looks, energy and charm had led him into the various interconnecting Parisian literary circles centring around Stein, Pound and Joyce. Mellow’s book is at its best here, capturing the vibrant atmosphere of a seminal time and place in cultural history, one of those strange and inexplicable brush fires of genius. It was Stein who proved the most influential on Hemingway, helping him hone his distinctive style, all gerunds and elegant connectives.

Literary style wasn’t the only thing Hemingway forged in Paris. He also constructed the faux-primitive mask that he was to don for the rest of his life. Far from being some crude yet gifted Caliban, who dazzled the world-weary Europeans, Mellow’s Hemingway is a clever, supremely self-confident careerist, a born expert at the intrigues of literary politics. While in Paris, he skilfully prepared the ground for his first two novels, The Sun Also Rises and A Farewell to Arms, both written before he was 30. Unfortunately, he would never write as well again.

With early success, the young writer became increasingly obsessed with his image. Like Stein, Pound and Eliot, he had brought with him to the Old World the very New World notion of personal re-creation. It is this lifelong manipulation of his persona that is the central theme of Mellow’s study. Just as Hemingway the novelist would take the crude stuff of his experience and transform it into art, so Hemingway the man used his talent and notoriety to create a public self that was in many ways at odds with his private one. It is to Mellow’s credit that he is consistently able to look behind the mask, to see the weakness, sensitivity and humanity there.

For instance, Mellow consistently equates Hemingway’s notorious queer-bashing and frenetic macho activity with the strong hints of repressed homosexuality in his work and his often stormy relations with male friends. Similarly, the obsession with the stylised violence of war and bullfighting has as much to do with his own self-doubts and fears as it has with the concepts of the heroic and grace under pressure. Just as Hemingway’s sparse prose cloaked great complexity, so his often boorish behaviour concealed his considerable contradictions in his character.

This constant need to walk a personal tightrope also proves a good explanation of Hemingway’s mercurial treatment of friends. Although Mellow never makes this point explicitly, his evidence indicates that Hemingway’s eventual breaks with Fitzgerald, Stein and Dos Passos had less to do with personalities and professional rivalries than with the fact that they had all glimpsed the real Hemingway, the insecure artist struggling to keep a grip on his fading talent, a reality very much at odds with the image of the self-confident sportsman which was spoonfed to readers of Life magazine.

Interestingly, it was far easier for Hemingway to maintain a lifelong relationship with Pound, whom he rarely saw, yet corresponded with regularly. The great white hunter of American letters was a master at covering his tracks with words.

His later years make for dispiriting reading. Hemingway had once written how his fictional doppelganger, Nick Adams, had longed to live a life “without consequences”. Sadly, the elder Hemingway appeared to be obsessed with nothing but them, staging media events and badgering would-be biographers as he tried to jury-rig his place in the pantheon.

As Edmund Wilson tellingly stated, the public Hemingway was “certainly the worst-invented character to be found in the author’s work”. Hemingway’s coverage of the Spanish civil war is energetic yet politically naïve, while his correspondence from the second world war is something of a farce, as if he believed the war was being fought for his benefit. Bad writing, bad relationships and bad drinking followed, with the great success of The Old Man and the Sea depicted here as basically an accident.

The myth reaches its apotheosis in Idaho when Hemingway, depressed and paranoid, places his trusty shotgun against his forehead and pulls the trigger, finally cracking that durable mask he had moulded more than 30 years earlier in Paris.