- Edward Said

i.

This is the sound of a landscape of ice. Recently, my friend told me how – in the northern reaches of Norway – the fjords sang. Structures sing; cities sing, give life, and take it away. Bodies come close to other bodies, enter their worlds. And for hundreds of days – thousands – these cycles are repeated. This is the sound of a history re-entering an orbit, dragging close to the thick lump of a planet's heart.

ii.

“Southlite” by Pablo's Eye is an expanding wave; if you imagine a wave, splitting – radiating outwards – from the epicentre of an opening, an initial analogue shunt. This is the dry cough of a synthesizer before it has been tooled, equipped, prepared. We're being “let in”, but let in slowly. The ice melts, creaks, and yawns open its skin to let out ships which – not even ghosts any more, or skeletons – plough.

A sound unwinds, between the uncaught stands of grey-white buildings which broadly constitute the city of London, and of those parts of London which are not yet London or were, once, a part of London. In this landscape the speaker-composer descends throughout its entire sonic texture (again, a wave, breaking) with the conscience of a field recordist, ear plucked and levelled keenly to these attuned waves which break and break over and through her. Ambience builds, sustains, accumulates – we are entering a language place in addition to a sound place, a confluence of sound and linguistic texture. Words parr and split through the fruit's skin, if you imagine a fruit.

The first part, it gives a hypnotic dub inflection, warped & echoing; against a fading incurring drumming, distressed like train wheels going over points, gaining intensity, flanging at its outer edges; becoming more conspicuous, becoming less certain of itself – a derailment of sorts, which our - “the” - voice attends to, calmly, certainly, as if all of this were known and predicted; a vase of water poured exactly into a cup that fits it, without spillage, without missing a drop.

Other notes – girded by War of the Worlds-like B-movie thrusts into (no, from) the dark, contain within them a middle-eastern vibrancy, as if applying themselves not to conventional tonality but to the semitone, to microtonality. Great housey beats crash into the mix (or do they emerge from it?) in slow time, always echoing; if it is house then it is the club, 1993, after the ravers have gone home, sunk in mist, back to bedrooms, behind doors. A drum continues, lapses, rises. This is a good thing; we're treading into accident, something heard from another room that we are not hearing, or should not be hearing, or are not welcome to hear in the first place. We are immensely lo-fi, slightly in slow motion, beckoning. A choral organ is summoned, as a violin arches across the cobalt, singing. It is a hypnotic sound, a drugged sound, constantly veering into and away from the light. The narrative picks up, is dropped, and occurs again.

Why am I watching the past? Can I pause, transform, transfix this thing? I am walking into the night, up a flight of stairs; a crane is turning, car headlights streaming red amber pulses.

“It is early morning; he begins to make out sounds, as if someone were turning the volume up in his head. He hears a constant stream of traffic.”

“Southlite” can be conceived of as collages of sound; brought together, in continuous and surprising rearrangement. But it doesn't clarify a specific sonic architecture; it remains an exquisite corpse, generating toward mystery and obscurity; unlike the deceptions of deep house melody-making (and it is not shy of its debts here), it listens you toward its centre. Dragged-out, echoing bass has the tonal thickness of Augustus Pablo, roots reggae cascading (again, out from) an ambient pull and drawl. It has the deep and echoing array of “human mesh dance”, the sound-stage decomposed away from a recording studio and into a city; unbounded by sound-insulating tiles, it allows the sound to disappear itself and to refract back onto the listener in jubilant, frightening, melancholic spears.

The “depthless contemporary” moment which Mark Fisher spoke of is engrained throughout every texture of Pablo's Eye, the ultimatum without a language to convey it; we have arrived (are arriving) within an assemblage culture of disfigured parts, which nonetheless shuttle forward or give the impression so, as if only by lazy assumption that a new day heralds forward movement. The cancelled future. The speaker-composer is lost, abridged and taken apart as they confront the myriad workings of a culture as undifferentiated material without visible structure and relationships.

There are newer, and tighter, structures which arch throughout the work; I kept pairing “Southlite”, in my listening to it, with Sister/Body, the Czech-Slovak techno experiment. I am pulled back toward early/late echoes of Massive Attack, a deep shuddering course.

iii.

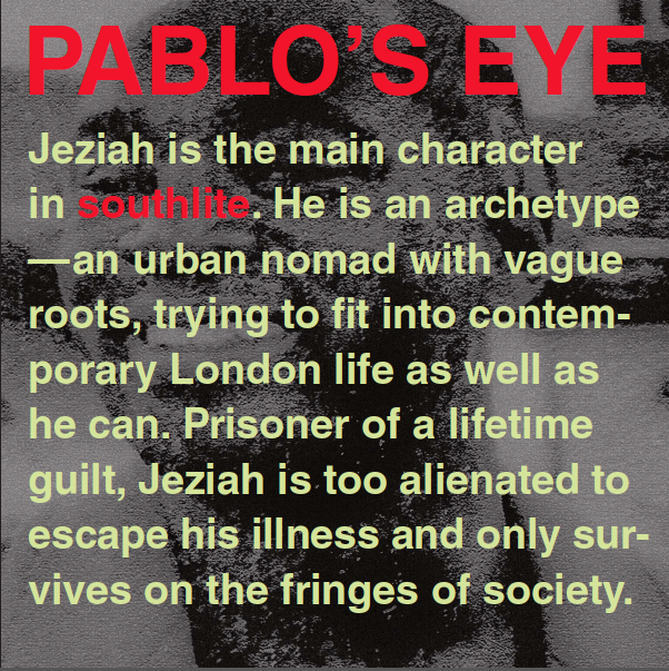

Originating from Belgium, and founded in 1989, Pablo's Eye consists of six artists working across mediums and technologies, instruments and forms. Voice, guitar, violin, samples, text. Translated and edited by writer and poet Richard Skinner, the words sway earthly – and often transparently – through the myth-smoke of the long, slack chords and pulses of the record's structure. The central figure – fictive, Everyman, specific, real – is Jeziah, yet the possessive voice talks both about a person (“he”) and about another. “It is early morning”, a deliberate observation; record; archive. “All around me” is followed by “Voices”, as if the two songs, in title and imaginary, are part of the same conversation. The original soundtrack was composed in 1999 for an abandoned film, which itself was intended to be a collage; a fitting visual structure for a musical composition which is more than any OST, but rather a mirror-montage. Jeziah is a figure arriving, given a place; flat 1109, sights of the docks, with cargo and papers. Jeziah throws himself ultimately to the police, entering what the album calls his “darks”; a sense of guilt, loss, rage, abandonment, confusion. Jeziah is a migrant voice, tossed and moving, both purposeful and lost. “Southlite” was based on a text for a novel by Skinner – also called “Southlite” - and is testament to a subject living on the fringes of society; all about him is a density of living and complex lives, yet he is constrained and pulverized by them. “Southlite” is an appropriate lyrical and compositional moment at a time when migrants – dying, dead, barely alive, desperate to live – arrive on numerous shores to seek refuge in a society which blunts them, turns them away, rejects them within itself. Jeziah has been coming – and going – for centuries. He is arriving again, now. In a recent exhibition at the Triennale of Milan, the exhibition included a film; the film followed in decayed wavering shots people subjecting themselves to the sea, and being pulled down into it as the rock of Gibraltar crested on the distance. The music was of water entering the field of sound; crushing, but voices could be made out against it. The film was projected across walls, across mirrors. “Southlite” is mirror and water; it is the city after its levies have broken, the streets erupting in proximity and distance. Jeziah's story – a story in fragments, in smashed continuities – is mesmerisingly conveyed in a composition and story which teeter on the edge of comprehension, and invite us to give empathetic witness to their happening; as drums – loose, beating, dub – reflect the rhythm of traffic, they also reflect the rhythm of a mind which is passed by that traffic. To dance to it is to be pulled in, lured; yet its core constantly threads away from us, the fragment arising in the ascendant. That the film project never came to fruition is a melancholy reflection on Jeziah's own failure-to-become within his new society. Throughout, I kept returning to a line by Ocean Vuong, also reflecting on coming and going, on colonial history, on now:

“the song moving through the city like a widow”

“Southlite” is both song and widow; movement and stasis. At least – in listening – we reactive that movement, and allow it a possibility to continue there.

OMGV, May 2017

Owen Vince is a writer, digital artist and electronic musician. His recent releases include 'body without organs' (Harsh Noise Movement, 2017) and 'sometimes, frequency' (Illuminated Paths, 2016). He tweets @abrightfar.