- He was what the French call un triste. (p.8)

- One cannot use the life to interpret the work. But one can use the work to interpret the life. (p.9)

- Once, waiting for someone in the Café des Deux Magots in Paris, he managed to draw a diagram of his life: it was like a labyrinth, in which each important relationship figures as “an entrance to the maze”. (p.10)

- The self is a text—it has to be deciphered … The self is a project, something to be built. And the process of building a self and its works is always too slow. One is always in arrears of oneself. (p.14)

- Precisely because he saw that “all human knowledge takes the form of interpretation”, he understood the importance of being against interpretation wherever it is obvious. (p.18)

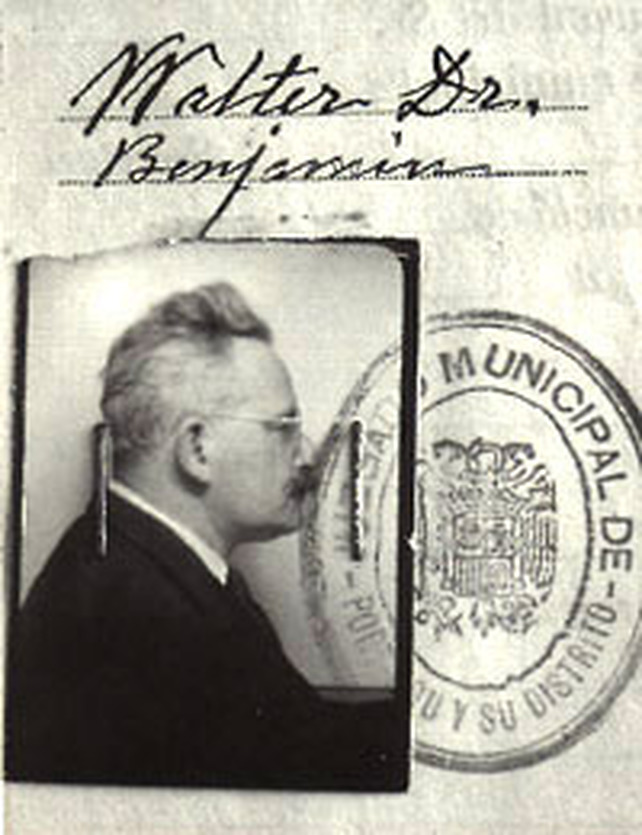

- The need to be solitary—along with bitterness over one’s loneliness—is characteristic of the melancholic. To get work done, one must be solitary—or, at least, not bound to any permanent relationship. Benjamin’s negative feelings about marriage are clear in the essay on Goethe’s 'Elective Affinities'. His heroes—Kierkegaard, Baudelaire, Proust, Kafka, Kraus—never married; and Scholem reports that Benjamin came to regard his own marriage (he was married in 1917, estranged from his wife after 1921, and divorced in 1930) “as fatal to himself”. (p.23)

The idea of the flâneur

- The street, the passage, the arcade, the labyrinth are recurrent themes in his literary essays… (p.9)

- “Not to find one’s way about in a city is of little interest … But to lose one’s way in a city, as one loses one’s way in a forest, requires practice…” (p.10)

- The recurrent metaphors of maps and diagrams, memories and dreams, labyrinths and arcades, vistas and panoramas, evoke a certain vision of cities as well as a certain kind of life. Paris, Benjamin writes, “taught me the art of straying”. (p.10)

The influence of Saturn

- “I came into the world under the sign of Saturn—the star of the slowest revolution, the planet of detours and delays…” (p.8)

- The influence of Saturn makes people “apathetic, indecisive, slow” … Slowness is one characteristic of the melancholic temperament. Blundering is another, from noticing too many possibilities, from not noticing one’s lack of practical sense.” (p.11)

The role of memory, time & space

- Benjamin could write about himself more directly when he started from memories, not contemporary experiences… (p.12)

- Benjamin regards everything he chooses to recall in his past as prophetic of the future, because the work of memory (reading oneself backward, he called it) collapses time. There is no chronological ordering of his reminiscences, for which he disavows the name of autobiography, because time is irrelevant. (“Autobiography has to do with time, with sequence and what makes up the continuous flow of life,” he writes in 'Berlin Chronicle'. “Here, I am talking of a space, of moments and discontinuities.”) (p.12)

- Memory, the staging of the past, turns the flow of events into tableaux. Benjamin is not trying to recover his past, but to understand it: to condense it into its spatial forms, its premonitory structures. (p.13)

- For the character born under the sign of Saturn, time is the medium of constraint, inadequacy, repetition, mere fulfilment. In time, one is only what one is: what one has always been. In space, one can be another person … Time does not give one much leeway: it thrusts us forward from behind, blows us through the narrow funnel of the present into the future. But space is broad, teeming with possibilities, positions, intersections, passages, detours, U-turns, dead ends, one-way streets. Too many possibilities indeed. (p.13)

The idea of the miniature

- Much of the originality of Benjamin’s arguments owes to his microscopic gaze … “It was the small things that attracted him most”, writes Scholem. He loved old toys, postage stamps, picture postcards, and such playful miniaturizations of reality as the winter world inside a glass globe that snows when it is shaken. His own handwriting was almost microscopic… (p.19)

- To miniaturize is to make portable—the ideal form of possessing things for a wanderer, or a refugee. Benjamin, of course, was both a wanderer, on the move, and a collector, weighed down by things … To miniaturize is to conceal. Benjamin was drawn to the extremely small … To miniaturize means to make useless. For what is so grotesquely reduced is, in a sense, liberated from its meaning—its tininess being the outstanding thing about it. It is both a whole (that is, complete) and a fragment (so tiny, the wrong scale). It becomes an object of disinterested contemplation or reverie. (p.20)

On style

- His characteristic form remained the essay. The melancholic’s intensity and exhaustiveness of attention set natural limits to the length at which Benjamin could explicate his ideas. His major essays seem to end just in time, before they self-destruct ... His sentences do not seem to be generated in the usual way; they do not entail. Each sentence is written as if it were the first, or the last … His style of thinking and writing, incorrectly called aphoristic, might better be called freeze-frame baroque. (p.24)