If Agnès Varda’s 1985 movie Vagabond is like any other movie, then it would be Citizen Kane. When you’ve seen both, you see that Varda almost certainly used the structure of Orson Welles’ 1941 movie as a blueprint for her own. Both start with a death, both are an investigation into a life, both end inconclusively.

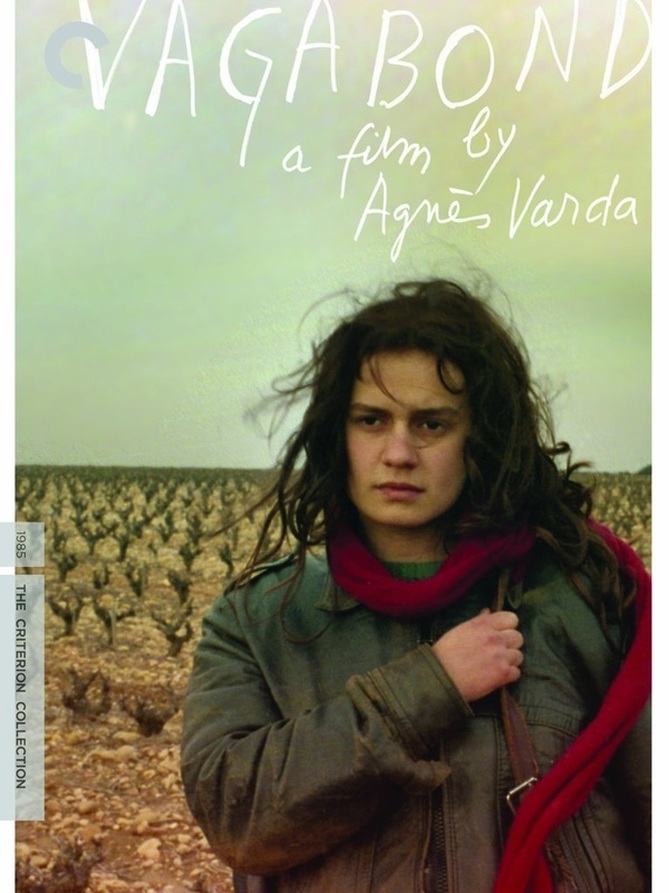

Vagabond is about a young woman, Mona, played by Sandrine Bonnaire, who has perished from the cold, and the attempts by numerous people who crossed her path to assign meaning to her chosen way of living. There are 18 ‘visions’ of Mona presented by those who came across her. The film is a series of gazes, of one-way exchanges from different people—dropouts, hippies, a prostitute, an itinerant worker, a maid (the ‘punctum’ moment when the maid addresses the camera directly)—but each of these ‘witnesses’ is not seeing Mona, but a reflection of their own regrets, secrets, longings. As the film makes transparently clear, Mona refuses to be co-opted into any image they may have of her. She defies identification and empties the mirror of any meaning. Her peripatetic and solitary existence (‘I move’) is a deliberate choice and functions metonymically for her unfixability. Mona is the blank centre of the film and she leaves no trace of her existence.

In Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962), Agnès Varda made frequent use of tracking shots to follow Cléo along Parisian streets; there is a lot of the same kind of camerawork in Vagabond. But while the narcissistic Cléo is nearly always in the center of the frame, Mona can barely stay in the picture. As she walks along beaches, streets, fields—confirming the viewer’s sense of her restlessness and rootlessness—she either walks into the frame of an already-in-motion tracking shot, or falls behind, or walks out of frame as the camera keeps moving. It’s as though she is on the periphery of her own movie. Varda says, “The whole film is one long tracking shot … we cut it up into separate pieces and in between them are the ‘adventures’.” There are 14 of these highly formal tracking shots and they all frame Mona at some kind of juncture. They are Mona’s ‘signature’.

In fact, we never actually see the “adventures” that Varda speaks of. The other distinctive feature of the structure of Vagabond is its highly elliptical editing. Huge chunks of time are simply omitted from the movie and so we have little or no idea of what has exactly happened between these tracking shots. Suddenly, nothing happened. But of course it isn’t the case that nothing has happened, it is only that the exact nature of what has happened remains uncertain. We are therefore plunged into a world of sporadic, discontinuous conversations, of remarks that miss their target, of looks that do not engage, of relationships that develop erratically. The form of the film mirrors its content and the elliptical editing prevents the viewer from establishing any motive for Mona’s actions—indeed, they help to preserve her secrets.

Vagabond is set up in the same way as classic detective movies such as Murder, My Sweet, Sunset Boulevard and the aforementioned Citizen Kane. The beginning of these movies sets up an enigma: “Who is the dead person?” We then flash back in time to find out how and why the death happened. The 18 witness accounts in Vagabond can be read as statements in response to the police’s attempts to find out what happened to Mona. But, of course, we have seen what has happened to her and so, for us, the central question in Vagabond is not ‘how’ or ‘why’ but ‘who’, a question that remains unanswered by the film’s end. We are privy to Mona’s gradual decline but her identity remains shrouded in mystery.

Although Vagabond sets itself up as a classic murder mystery, that genre and its traits are quickly abandoned. More accurately, Vagabond borrows many of the traits of the road movie, but of a distinctively European kind rather than, say, Easy Rider. Near contemporary movies such as Tarkovsky’s Nostalgia (1983) and Alain Tanner’s In the White City (1983) are similarly about characters in a state of self-imposed exile and contain similar highly-choreographed tracking shots.

I first saw all three of these movies when they were given a cinema release, though I was too young then to fully appreciate their subtlety and sophistication. But they stayed with me. They are ‘writerly’ films—films that explore contingent states of being—rather than ‘readerly’ films, which allow easy access for viewers by conforming to the idea of causality in plot. I knew there was something in them that I would only understand in time and I now see that Mona’s independence from a fixed identity is an assertion of her ‘otherness’, her différence, and it is that which makes Vagabond a proto-feminist film.

Most put Agnès Varda into the French New Wave, with Godard, Truffaut, et al, but the subtlety of her camera-stylo places her more properly in the Left Bank movement alongside such literary filmmakers as Alain Resnais, Chris Marker, Marguerite Duras and Alain Robbe-Grillet. Further emphasising this root in literature, Vagabond is dedicated to Nathalie Sarraute, a nouveaux romancier whose texts challenge conventional plot and characterisation, focusing instead on the physical sensations and ‘tropistic’ movements that subtend human interaction.

To its (open) end, Vagabond maintains the enigmatic mystery of an incomplete jigsaw puzzle. It is a unique mix of fact (Varda’s film was based on a real-life vagabond Varda had met) and fiction, documentary, a road movie told in flashback—so many different kinds of text beautifully interwoven and rewritten into a highly distinctive structure that Varda herself has described as ‘cinematic writing’, or cinécriture.