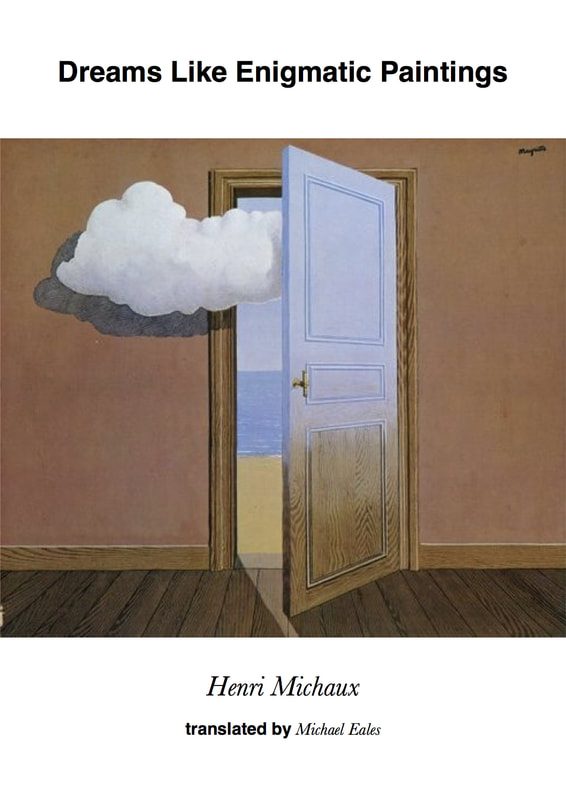

In The Courage to Create, psychologist Rollo May insisted that ‘the first thing we notice in a creative act is that it is an encounter’. It could be, he said, with ‘a landscape, an idea, an inner vision, an experiment’, but what would mark it out would be its intensity, for ‘genuine creativity is characterized by an intensity of awareness, a heightened consciousness.’ Henri Michaux’s collection of prose poems, Dreams like Enigmatic Paintings, newly and exquisitely translated here by Michael Eales, could not be a more perfect example.

The poems were Michaux’s response to the paintings of Réné Magritte, which in their urbane strangeness might have been expressly made to fascinate and bemuse him. The 1950s had been taken up by an alliance between Michaux and mescaline, a response to the horrific death of his wife in 1948 when she accidentally set her nightdress on fire. For more than a decade, Michaux experimented attentively with hallucinogens, recording his experiences in both text and drawings, and these works made his artistic name. But now, in the early 1960s, he was ready to meet with something new, weird and wonderful. Michaux was interested in the farthest outreaches of his mind, and Magritte’s art provided an intriguing mode of transportation for a melancholy poet. ‘More than anything, I wanted to know where these paintings would lead me; how they would support me; how they would thwart me; what inner desires they would arouse,’ Michaux writes in his forward to the text, concluding paradoxically, ‘Having only found so few paths, I regret that there are so many.’ The result is 31 brief poetic explosions, arresting, bizarre and inexplicable. There is no need to know anything about Magritte, or about Surrealism for that matter, to read them, for the manner of their genesis is an instruction to the reader as well. Just as Michaux fell upon Magritte by chance and let the shock inspire him, so the reader needs to approach these prose poems with an open and flexible mind, ready for an imaginative workout. What matters is to encounter them on their own terms and see what mental alchemy results.

Henri Michaux is one of the more clandestine figures of twentieth-century French literature, consistently avoiding anything that looked like limelight during his lifetime. Yet he was extraordinarily prolific, publishing over 60 works across a number of genres including poetry and travel writing, books of aphorisms, art criticism and his accounts of drug use, many illustrated by his own drawings. He has been described as a French Kafka, for the world of his imagination is full of hostility, aggression and fear. Inner demons fascinated him, and he was often obsessed by the idea of our inevitable isolation. Michaux found failure a great deal more convincing as an experience than success, which led to an art characterised by attrition, dissipation, perplexity, disintegration. He took up painting in the 1930s because of his frustrations with the closed circuit of language, but as both poet and painter he spoke from the place of being overwhelmed by the infinite, unknowable world. What makes his work powerful is that there is nothing performative or sensational about this evoked emotional state. Michaux was a quiet man who shunned all extravagance and his art is unsettling because of its genuine, subtle depth. Writing in the Guardian, Octavio Paz put his finger rather brilliantly on Michaux’s essential quality: ‘Painting and poetry are languages that he has used to try to express something that is truly inexpressible [...] All his efforts have been directed at reaching that zone, by definition indescribable and incommunicable, in which meanings disappear. A centre at once completely empty and completely full, a total vacuum and a total plenitude.’ I think this sums up Michaux’s inner contradictions well - a man of great humility, grafting away at the impossibly ambitious goal of describing the devastating extent of our limitations.

So it’s no surprise that, having sought a form of meditation in Magritte’s paintings, Michaux begins his preface to the text with the confession that time spent with the images has given rise ‘to dreams ...and confusion. The baffling painting is a starting point which stops dead.’ The Surrealist critic, Renée Riese Hubert has described Magritte’s paintings as being full of elements from an imaginary world ‘in search of a storyteller.’ But when Michaux offers himself for the role he shows both how intriguing and impossible it is; there is an abrupt and truncated feel to many of the poems, which open with an arresting image whose mesmeric quality refuses explanation. The marble sculpted head, for instance, that starts to bleed:

‘On the white shadowless face, a memory makes its mark, at first secretly, now betraying itself. The blood springs from the wounded soul.’

Or the tree stump that grows around the abandoned axe:

‘In the clearing, near the tree that lies felled, the stump has taken possession of the woodcutter’s axe. One of the gnarled roots, or rather one of the low woody supports, must have moved slowly and, like a bear’s paw, placed itself on the murderer’s tool, holds it and will never give it up. Justice at last. Equality. A new assertion.’

These have the quality of twentieth-century rewritings of the Brothers Grimm, dark fairy tale with a hint of twisted morality. In many of the poems there’s a magical or mystical animation taking place, the ‘rose that becomes a person’, for instance, or the person who becomes a house, or the door in a house undermined by an earthquake: ‘Its silly, pretentious, impassive rigidity was not maintained. As if finally it actually experienced real emotion, it buckled - the geological movement of a door - submitted to the unexpected, and frightful crushing and tearing.’ The innards of the poems are never simple, never static, instead there is this constant shape-shifting at work, whose guiding force is that of dark, troubled emotion. Nothing is safe from this kind of feeling, Michaux seems to be saying, not even sticks and stones and the rest of the inanimate world. It will find a way to seep in and destroy and become, as he writes of the tree roots, ‘A new anxiety for mankind.’

What we’re really talking about here is the uncanny. André Gide described how Michaux was fascinated by ‘the strangeness of natural things and the naturalness of strange things.’ In this respect, he and Magritte are speaking the same symbolic language. Aside from a few images that will remind anyone with a passing interest in Magritte of some of his more iconic paintings - a nightdress sporting a pair of breasts, clouds floating in strange places - it’s easy to forget the original source, and not really necessary to recall it. But for both Michaux and Magritte, the everyday familiar world has terrific power to unsettle. ‘Nothing but the banal can support the unusual,’ Michaux writes, stating further on in the same prose poem that ‘The extraordinary has not succeeded in overcoming the ordinary.The ordinary has not been defeated by the absurd.’ This is a reasonable judgement to pass on the entire collection; Michaux’s skill in these poems consists in creating delicate tension between the ordinary and its potential to be fantastic, unsettling and bizarre.

Michaux achieves this by crafting poems that resonates the same way dreams do. It’s in our dream life that we regularly meet the ordinary transposed into the fantastic. Every element of a dream is tinged with both significance and absurdity. Dreams beg to be interpreted, yet often resist, they are full of strange metamorphoses, and even the most humble and ordinary object within them can reveal secret energies. The poems in this collection reveal the exact same profile. There’s a clue in the title of the collection, after all, and the dream speaks to us as a special kind of encounter with our own disturbing, unsuspected creativity.

Although Michaux was never a fully paid-up Surrealist, (they were mostly performative, sensational and excessive, the opposite to Michaux) he was more than ready to acknowledge his debt to the movement: it gave him licence to focus in on the parts of psychic experience that most interested him. What Surrealists thought was useful about dreams was very different indeed to what intrigued Freud about them, as became apparent when André Breton wrote enthusiastically to the father of psychoanalysis about his work. For Freud the dream was full of meaning that could be interpreted in an entirely practical way and applied to the dreamer’s waking problems. For the Surrealists, the dream was an extension of the real world, a form of perceptive revelation identifying something in the real that normality otherwise veiled. For this reason, Breton believed the dream to be a call to revolution (this perplexed just about everyone at the time). But for the same reason, other Surrealists simply enjoyed the dream for its funky weirdness.

The poetic value of the dream for Michaux can be found in the powerful dynamic of transformation, in startling images and the trappings of the uncanny, but I think his strange habit of undercutting the complexity of his images with sudden brutality also needs to be taken into account. ‘Everything here is of equal value, that is to say no value at all,’ Michaux writes in one poem, ending another: ‘But nothing happens. Everything has already happened; has stopped for who knows how long.’ The reader is left on the wrong foot, in radical ambivalence, wondering what to make of it all. Reading the poems, I began to feel that these abrupt and frustrating closures were the equivalent of the poet bumping into the frame of one of Magritte’s paintings - or waking up disoriented from the dream. It made me think of Octavio Paz’s insight into Michaux’s desire to put us in touch at once with both total plenitude and total vacuum, on the borderline where meaning disappears. There is no more unsettling collapse of meaning than the moment of waking, where what was once so vivid now becomes ephemeral, ungraspable and haunting.

These aren’t readily accessible prose poems; Michaux never sets the reader an easy task, and at first they can seem too cerebral, too absurd. They require a certain kind of mental gymnastics, and a willingness to enter the poetic space without trying to control it. But this is also what makes them beguiling. They are radically different to the kind of art that’s being produced today and open up the imagination in surprising ways. For me, Michaux’s dream-like prose poems are an impressive example of his poetic quest to find both a total plenitude and total vacuum of meaning. We are lucky to have them in this excellent translation, which manages to retain both the ordinariness and the peculiarity of every Michaux sentence. No mean feat, and one that allows the reader fully to experience the shivery oddness of this work.

Victoria Best, author of An Introduction to Twentieth-Century French Literature (New Readings Series)