At any rate, the magic is a magic of voice, its rhythm, its pitch, its capacity to transport.

The Legend of the Necessary Dreamer, to borrow a favourite word from Antonin Artaud, is 'telluric'. It is a book about bells, dreams, memories, architectures, cities, houses, peacocks and earthquakes. Things radiate and reverberate in it. It is an affective read. The reader is bombarded with space, tripped out on signs, disorientated by stucco. The ethos is sculptural; the logic Orphic. You are moved around; the text sings. Bells speak, dust articulates, earth tremors seek intimate discourse. There is also, I think, an attempt to resurrect the dead.

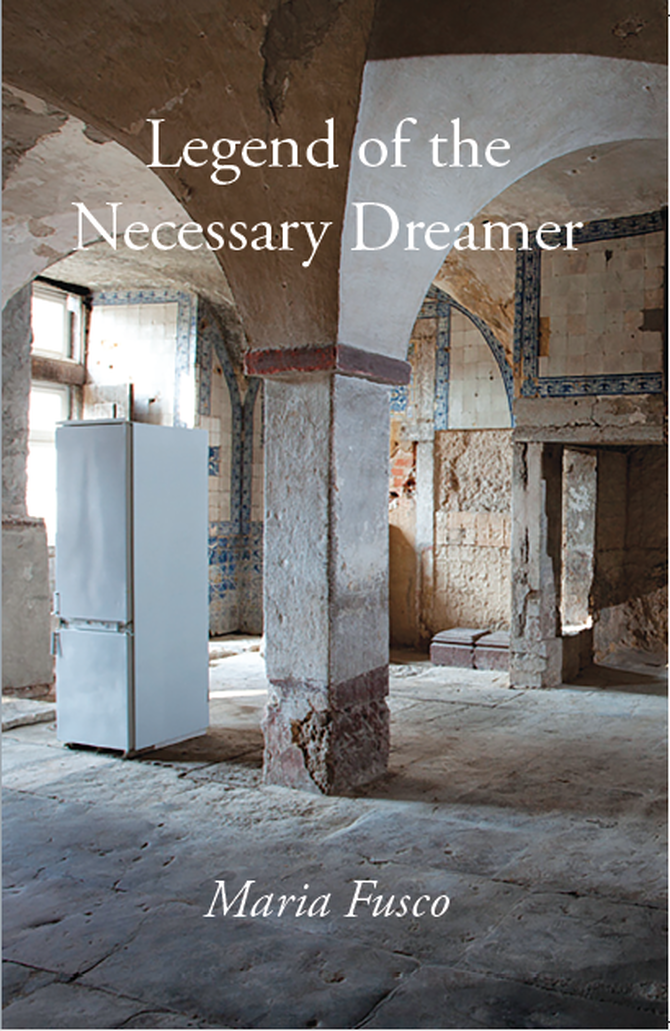

This is a book for our time, the Anthropocene. The setting in Lisbon, in the labyrinthine rooms of the Palácio Pombal, is no coincidence. Lisbon’s earthquake and tsunami on 1 November 1755, All Saints Day, mark a moment of profound ontological and epistemological rupture in the European project. We are haunted by Lisbon. The moment when the earth speaks back, a ‘quake in being’ that Immanuel Kant repressed and Voltaire was astounded by. In the very heart of the Enlightenment, with its myths of progress and science, Lisbon showed that the end was in the beginning – that matter is not only brilliantly vibrant (Jane Bennett), but molten, dangerous, dark. It can destroy you.

In the face of Lisbon, more than two centuries after the event, Fusco’s poetry is a poetry of equivalence, language that seeks to speak the secret language of things – walls, floorboards, beams. Like Virginia Woolf before her (To The Lighthouse) Fusco is, I think, a Deleuzian. Her writing expresses the world of matter, producing haecceities and refrains, making the world expressive – and thus, perhaps, liveable. If you want to understand The Logic of Sensation read The Legend of the Necessary Dreamer. This is fleshy writing, writing as meat and bone. There are no abstract concepts. Fusco performs theory, making it her own, sending it off, always and again and again, on some dizzy line of flight, the revenge of the aesthetic. Only the work of Lisa Robertson gets close. History, philosophy, theory: thinking through the lyric.

The book is a book of fragments and slippages. Words, sentences, clauses are always liable to implode, collapse, and go molten. The text is like lava, stone that flows. There is profound generosity in this quest for equivalence, an openness to the non-human world, a search for some kind of intimacy. And yet there is also, too, how could there not be?, a reckoning with grief, an articulation of loss. In one of her daytime reveries, Fusco says:

'To walk on history. To believe I am walking on history. I am concerned the floor will not remember me… Where the nails have hit home, a split transpires in the oak, and this marking of time, of time creeping through organic substance makes me mope.'

Fusco’s writing is distinctive, easy to recognise as hers, the persistence and distribution of a voice in diacritics. The sentences are full of brio, confident, up front. They astound and declaim: ‘We human creatures must find our match in scale’. But this frontality is a lure. As the eye follows the signs, easy meaning unravels, the texture start to bevel, and suddenly you find yourself through some seductive opacity, lost in a logic of language alone, a logic, that like the texts of Rimbaud, Genet, and Patti Smith, affirms that all reality really is just language, and vice versa. Politics is at work here, too. In Portugal, a country of conquest, and Lisbon, a city of empire, Fusco makes us feel like strangers in our skin, foreigners in the house, shipwrecked on the shores of a Europe full of cracks, crevices and fissures, in which the walls are always already breached. An immense sense of hope rings out of the text, a pedagogy of affect, a bell that ‘persists in duty’, a clapper that cracks open power’s obsession with measuring the time of production. In the Legend of the Necessary Dreamer, time percolates and flows, it is a sky that no power can anatomize or set to work.

This is power of another order… maybe alchemy or magic would be better words….

Carl Lavery, Professor of Theatre and Performance, University of Glasgow