Muslimgauze is a musician named Bryn Jones, who died in 1999 at the age of 37.

Muslimgauze is the purest embodiment of the principles of dub that I’ve ever heard.

Muslimgauze produced the most delicate, shimmering, luminous dubs I’ve ever heard.

Muslimgauze produced the most brutal, ear-shredding industrial dubs I’ve ever heard.

Muslimgauze is Electro-raï, thick with percussion loops, live zarb routines processed through washing machine ambience.

Muslimgauze is HipHop, dreadnought dub, Industrial noise, Mego-style crackles, Technoid minimalism, Fourth World ambience.

Muslimgauze is voiceloops over heat ‘n’ dust instrumentals with raga drones & warping bass drums.

Muslimgauze is throbbing Arabic drumming, soft-edged dub bass, string drones, fragments of singing & guttural chanting in Arabic.

Muslimgauze is audio environments instead of songs; dub pressure—all bass energy & rhythmic complexity.

Muslimgauze’s studio techniques include repetition, non-developmental processes, drones, drop-outs & lots & lots of reverb.

Muslimgauze’s signature in the studio is his use of the drop-out.

Muslimgauze’s masterpiece may well be ‘Drugsherpa’, a delicate, shimmering, luminous 20-minute ghostly dub that uses found sound & processed field recordings of Middle-Eastern percussion.

Muslimgauze’s music on ‘Drugsherpa’ is so layered & textured that it ceases to be aural & exists almost solely in the realm of sight & touch.

Muslimgauze’s ‘Babylon Iz Iraq’ remix for Unitone HiFi’s track ‘Babylon’ is a dark unleashing of poltergeists & may well be his crowning achievement as a remixer.

Muslimgauze’s world of music has four corners: Edgard Varèse, Kool Herc, Asian Dub Foundation & Throbbing Gristle (whom he saw live when he was 18).

Muslimgauze is Tribal hypnotica, Transcendental exotica.

Muslimgauze doesn’t sound like anyone else; he was an originator, the devastating beat creator.

Muslimgauze’s productions are used by famed sound engineer Rashad Becker to sound check his PA; he says that Muslimgauze is the standard against which he measures all other studio material.

Muslimgauze: “I was once in a Pakistani restaurant in Belgium and they were playing modern Pakistani music. I recognized Bryn’s music in there. The way they cut their beats. When I came in, they turned it off and played traditional. And I said, ‘No no, it’s really good. Put on the original.’ Bryn really liked this music, he really respected it and made his own version of it. You cannot chop up tradition that easily, but he was capable of doing that. His sounds give the impression it’s loosely made, he distorts sounds, but it is someone in control to an extent that’s very rare. It’s like in martial arts, where someone’s swinging a knife dangerously, but he knows to a millimetre what he is doing. It’s just brilliant. He had this collage technique in one instance he had the reloading of a gun, and it was really well used; or giggling women, or crying women or the clapping of hands, it was edited so beautifully. All these layers have different stories. Through the whole CD you hear very deep stories; someone breathing, walking, and only if you listen carefully you hear that. These fine details, and like I said, the clapping of the hands and the loading, crying… strong images, simple, basic. You could also hear he’d been out listening to things. He said he was always in the studio, but that’s not true. These musical styles he used, that’s the sound of the time. He’d been tapping into things, but we don’t know where, how or when. The dub, the breakbeat, all these elements he used he must have listened to. He wasn’t disconnected, you could hear it.” —Geert-Jan Hobijn, founder of Staalplaat.

Muslimgauze: “was never sanitized. It was just full-on in-your-face, whether you liked it or not. Sometimes it was extremely uncomfortable, exacerbated by the fact that some titles had some very intense Middle Eastern things going on, it gave it that whole, very heavy underbelly—it was like a soundtrack to the hell of Gaza under Israeli occupation… But he wasn’t making music for a Middle Eastern audience. To me it was the breaking of rules that was the beauty of it, because it was coming from somebody heavily influenced by the East. I was a guy who played by the rules, but Muslimgauze forced me to re-evaluate everything. He didn’t play by any rules, he had his own thing going, that’s what sets him apart from everybody else. You can see now, years after his death, how his influence is still out there. Muslimgauze lives on in other people. He lives on in my heart more than anything else.” —John Bolloten, aka Rootsman.

Muslimgauze: “Even the slightest, prettiest tracks are inhabited (or inhibited) by an impossibly frail and inconceivably deep sadness—which, in truth, is hard to believe was entirely locatable in Jones’s feelings about a Middle East he never visited and so which always remained an infinitely restorable phantasm inside his head. The sadness seems much deeper and further ingrained than that, approaching pathological—almost as if the terrible dispossessed ‘birthright’ of the Palestinians corresponded, secretly, to some personal scar or shadow in Jones’s own life.” —Ian Penman

Muslimgauze recalls the black arts, magic, murk, mental disintegration.

Muslimgauze is an assault on the senses.

Muslimgauze is an explosion in the cortex, a detonation in the solar plexus.

Muslimgauze is a shadow, an X-ray.

Muslimgauze is the negative of a track.

Muslimgauze is whatever you think he’s not.

Muslimgauze is Punjab Root.

Muslimgauze is the Girl Who Sleeps with Persian Tulips.

Muslimgauze is the Fakir of Gwalior.

Muslimgauze is the Turkish Manipulator of Limbs.

Muslimgauze is Dharam Hinduja.

Muslimgauze is Feng Shui Orange.

Muslimgauze’s music is boundless.

Muslimgauze is sounds of the souk & radio muezzin.

Muslimgauze is a call to arms.

Muslimgauze is the ghost in the machine.

Muslimgauze is the duppy in dub’s machinery.

Muslimgauze is the turning of music inside out to show its seams.

Muslimgauze seeks out the concealed mechanisms.

Muslimgauze captures the sound of a machine’s malfunction.

Muslimgauze is reshaped & remodelled.

Muslimgauze is lowered, louvred & heavily modified.

Muslimgauze is food.

Muslimgauze is primal.

Muslimgauze is maternal.

Muslimgauze began as Muslimgauze after Israel’s invasion of the Lebanon in 1982.

Muslimgauze was born & lived his whole life in Swinton, Manchester & never set foot in the Middle East.

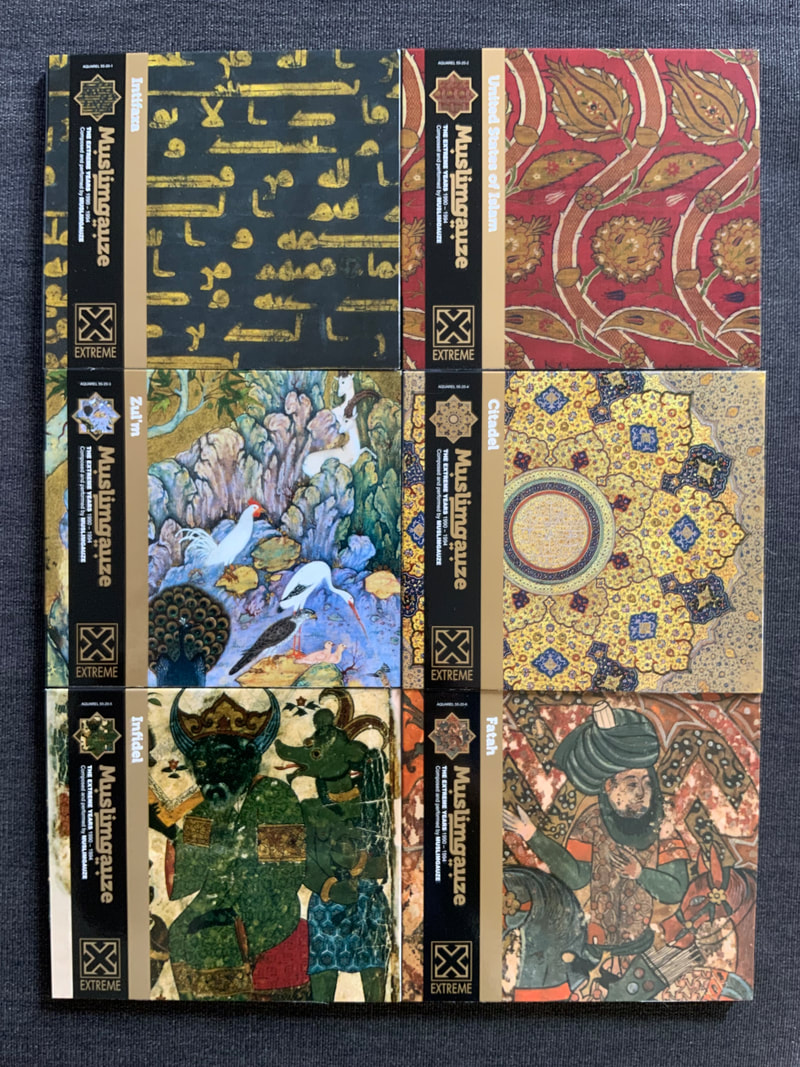

Muslimgauze’s cover images & album / track titles are militant Arabic agit-prop.

Muslimgauze’s political consciousness is extremely pro-Palestinian.

Muslimgauze: “There are no lyrics because that would be preaching.”

Muslimgauze is often criticised for his political beliefs.

Muslimgauze always wore black socks with black sandals, black slacks, a dark hoody that made him look like a modern-day monk.

Muslimgauze’s way of living bears a lot of similarities with the life of the French composer, Erik Satie, about whom I wrote a novel—both were one-offs, isolationist, totally committed to nothing other than their work.

Muslimgauze: “We work the whole time. It is like an illness.”

Muslimgauze has, to date, released more than 200 albums, with still more being released every year.

Muslimgauze is, without doubt, the most gifted, prolific artist, arranger & producer in the world of electronica ever since John Cage made ‘Imaginary Landscape No.1’ in 1939—a work for two variable-speed turntables, frequency recordings, muted piano & cymbal.

Muslimgauze’s reputation as an innovator & pioneer is secure, his influence can be heard everywhere today, for instance in the dub bulletins of B-dum B-dum Sound, Saint Abdullah, Vatican Shadow, DJ Marcelle, Holy Tongue & Dark Sky Burial.

Muslimgauze is Janus, the god of beginnings, gates, transitions, time, duality, doorways, passages, frames, endings.

Muslimgauze is a shaman, a sorcerer.

Muslimgauze is a Romantic.

Muslimgauze is the Mozart of the post-techno era.

*Bryn Jones would have been 62 in 2023. There are 62 entries in this essay, one for each year of his life had he lived.