After he made ‘Messidor’ in 1977 (a controversial road movie about two young woman who kill a man after he tries to sexually assault them), Tanner had a heart attack followed by heart surgery. Afterwards, he said he was through making didactic movies and emerged a few years later with ‘Light Years Away’, his first movie in English. This was in 1981 and the film marked my entry point into Tanner’s work. As an impressionable 16-year old, I remember watching it late one night on Channel Four. I vaguely remember it being set in a dilapidated petrol station in a post-apocalyptic world. The cast - including Trevor Howard and Mick Ford - was dressed in rags and there was a big bird which seemed to hold some great significance. It bemused me but I never forgot it.

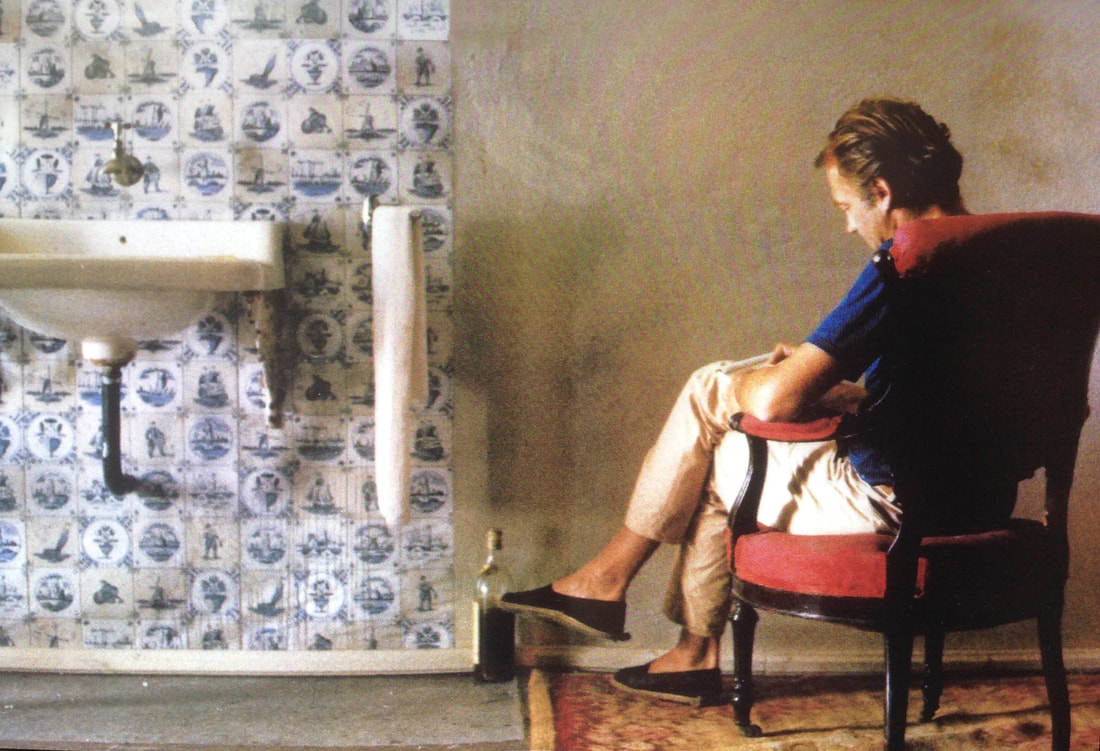

So, when his next movie came out a few years later, I went to see it in the cinema. The film was ‘In the White City’ and it made a deep impression on me which lasts to this day. The story is simplicity itself: a mechanic on an oil tanker, capriciously decides to jump ship at Lisbon. He spends the following few months wandering around the ‘white’ city, filming himself and everything he sees - the streets, tram rides, the sea - on a Super-8 camera. He sends these home movies to a woman (his wife?) in Switzerland, who has them developed and watches them. They are postcards from a man who is frozen in time and place, a flaneur who has no aim and no agenda, an unanchored sailor on the road to nowhere.

Nothing much happens in the movie. It is dreamy, largely without event or incident and therefore plotless. It was no surprise to learn that the film was completely improvised by Tanner and his lead actor Bruno Ganz. The film carries no screenplay credit. The pleasure of the film comes from this aimlessness. It’s a film about the moment, the here and now, without care or comment. Is the sailor having an existential crisis or has he found himself at last? We never know, but that’s not the point. On the aforementioned undergraduate degree, I wrote a paper on Tanner’s film and its use of those home movies. The movies are an exploration of space, not time, and so they ‘freeze’ us and force us jump out of the story, just as the sailor has jumped ship and is landlocked. The home movies gradually replace the film’s story-time itself as the nameless sailor’s being dissolves into the surfaces of the city - the stone, the breeze, the water, the white light and dust.

In the same year that ‘In the White City’ was released, Andrei Tarkovsky released his movie ‘Nostalgia’, a film with which Tanner’s bears a lot of similarities. In Tarkovsky’s movie, the main character (played by the late great Oleg Jankovsky) is also existentially ‘stuck’. Tarkovsky’s movie is devoid of plot, too. Set in and around the Roman baths of a small Tuscan town, the main events are a nosebleed, a rainfall, an argument, lighting a candle. Nothing happens and then it’s all over. Wonderful.

A couple of years later, Agnès Varda released her stunning movie ‘Vagabond’, in which Sandrine Bonnaire plays a young itinerant woman called Mona who, when asked why she drifts around so much, simply shrugs her shoulders and replies, ‘I move.’ The film is a series of gazes, of one-way exchanges from different people—dropouts, hippies, a prostitute, an itinerant worker, a maid—but each of these ‘witnesses’ is not seeing Mona, but a reflection of their own regrets, secrets, longings. Mona is the blank centre of the film and she leaves no trace of her existence.

All three of these movies are about characters in a state of self-imposed exile and all contain highly-choreographed tracking shots. For me, they form a loose trilogy of road movies, but of a distinctively European kind rather than, say, ‘Easy Rider’. When I saw these movies in the cinema, I was too young to fully appreciate their subtlety and sophistication. They are ‘writerly’ films - films that explore contingent states of being - rather than ‘readerly’ films, which rely on the idea of causality in plot. When I started to write fiction, I remembered Tanner’s film in particular. It taught me that you can write in real time, about inconsequential things, such as corners of rooms, billowing curtains, a night in a bar, the heat of the sun, a wall. Just moments, things, nothing more. We don’t have to be a slave to plot. It was a revelation.

I was fortunate to meet and interview Tanner once, in the early ‘90s, when his movie ‘The Diary of Lady M’ was screened at the BFI in London. He told me a story that evening which I’ve never forgotten. Some time in the ‘70s, in between film projects, he mounted a camera facing outwards on his car window and drove around his native Switzerland for days and days letting the camera run and run. He edited the footage down to around 8 hours of film of roadside views of streets, trees, houses, lakes, supermarkets, mountains, petrol stations, etc. He organised an evening with friends to show them the footage. After all 8 hours, every one of his friends was numb with boredom and they all urged him never to release any of it. He said he’d never been so disappointed with a reaction in his life. I laughed when he told me that story because I would have loved that film. A great artist, massively overlooked and severely underrated. Merci, Alain. Adieu.