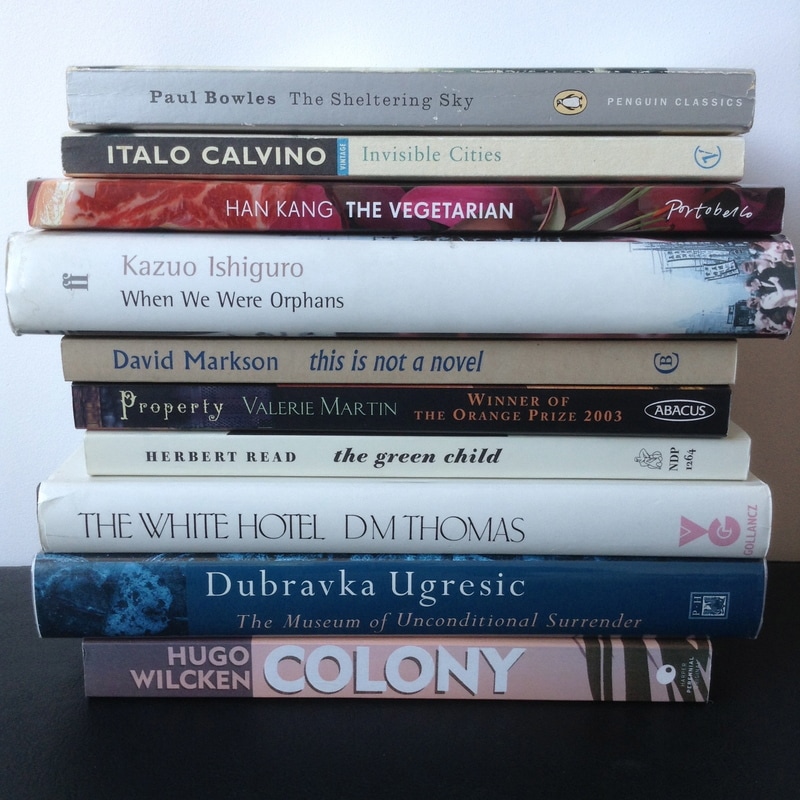

Paul Bowles’ The Sheltering Sky

In Bowles’ quasi ‘beat’ novel, two moneyed Americans arrive in Tangier just after the Second World War in order to rejuvenate their marriage. Port and Kit’s journey starts at the coast and goes directly into the desert, stopping at places that become fewer and further between and less and less well-populated until, ultimately, they arrive in the middle of nowhere. The desert and its ‘virulent sunlight’ take on an increasingly claustrophobic, emptying role, smothering love and hope until all that is left is sand and wind. This doomed journey into the desert is a subtle, sophisticated metaphor for this stunningly honest portrayal of a modern marriage.

Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities

As a young man, Italo Calvino read Marco Polo’s account of his travels to the Orient and had always wanted to write about them but he never knew how. Many years later, he found himself writing numerous microtexts of imagined cities. He had the idea of framing these descriptions with Marco Polo’s fabulous voyage to the Orient. At around this time, Calvino was invited to join OULIPO and his fiction began to incorporate that movement’s obsession with building complex mathematical structures into literary texts. Calvino believed strongly in the idea of a work of art as a map of the universe and the sum of all knowledge, a vocation in Italian literature that he said had been handed down from Dante to Galileo. Invisible Cities is no exception. Its multifaceted structure allows for multiple, non-hierarchical readings. It is the single work that embraces all his previous works as well as alluding to the Bible, classical literature, medieval texts, oriental literature and utopian/dystopian literature from Thomas More and Aldous Huxley. Most of all, it displays what Calvino learned best from Borges, namely that brevity can encompass infinity.

Han Kang’s The Vegetarian

The Vegetarian is about a woman who wants to become a tree. Set in Seoul, Part One, entitled “The Vegetarian”, starts in the first person from the POV of a man whose wife, Yeong-Hye, one day announces that she is now a vegetarian. Her husband finds this intolerable, as does her father and mother, and they seek to force her to eat meat. Yeong-Hye resists so strongly that she cuts her wrist in protest. Her family have her committed to a psychiatric hospital, where she stays for several months. Part Two, entitled “Mongolian Mark”, is set two years later and is told in the third person from the POV of Yeong-Hye’s brother-in-law, a visual artist who has formed a secret desire for Yeong-Hye ever since her attempted suicide. Part Three, entitled “Flaming Trees”, is in the third person and told from the sister’s POV. Yeong-Hye has been committed to a psychiatric hospital again and, as her sister travels to visit her, the sister thinks back to when she and her sister were young girls. It transpires that their father used to physically abuse Yeong-Hye, about which her sister has feelings of shame and guilt. While in hospital, Yeong-Hye tells her sister that she has completed her metamorphosis from animal to vegetal and is now a tree. The book ends with a vision of some trees on fire. As the novel progresses, we explore the strengths and weaknesses of the human relationships within the book. The sister, who was barely mentioned at the start, evolves into a main character. Her husband, also hardly noticed at the start of the book, comes forward to have his own voice before then disappearing from the narrative altogether. By the end of the novel, Yeong-Hye’s ex-husband (the entry point into the novel) has long since been forgotten. The men disappear, the women remain. The only constant is Yeong-Hye herself, although she doesn’t have a voice or her own vantage point in the narrative. She remains an enigma from start to finish.

Kazuo Ishiguro’s When We Were Orphans

I’ve read all of Ishiguro’s books but When We Were Orphans is my particular favourite. As a result of his love of the Sherlock Holmes stories, Ishiguro was keen to attempt a novel narrated from a detective’s POV but, in When We Were Orphans, we remain in the dark as ever regarding how his main character Christopher Banks actually solves any crimes. Indeed, in place of being aligned with a narrator who can never quite grasp the reasoning process of the great detective (e.g. Watson), our perspective is shifted to a detective-narrator whose subjectivity and emotion often overwhelm the rational aspects of his role as detective. Ishiguro’s narrative has all the trappings of the detective story, but none of the internal logic. Banks is another of Ishiguro’s ghostly, haunted narrators, an actor who wrongly interprets the reality around him.

David Markson’s This Is Not A Novel

This novel does what it says on the tin. Not a novel in the conventional sense—with a plot, characters and narrative drive—instead, it is a series of short, sharp quotations and observations that seek to touch upon and draw out the points of connectivity in the whole history of literature and culture. Imagine a spider’s web turned into a globe. Because of this wealth and scope of its material, this is the purest book I know and one I return to again and again and again and again.

Valerie Martin’s Property

Property is quite simply the most astonishing historical novel I’ve ever read and Martin’s narrator, Manon Gaudet, a listless southern belle from New Orleans, is one of the most fabulous creations I’ve ever come across. Set in the early 19th century, the novel revolves around Sarah, a slave girl who may have been given to Manon as a wedding present from her aunt, and whose young son Walter is living proof of where Manon’s husband’s inclinations lie. Property is a novel written on the fault line of race and racial tension and contains one scene of the most excruciating horror and violence I’ve ever read in a novel. It is also a highly elliptical book whose central mystery remains unsolved. Are those whisperings Manon hears behind the wall? If so, who is whispering?

Herbert Read’s The Green Child

A man in a black cape named Olivero is sitting on a train in 1930s Yorkshire. He looks totally out of place. He gets off at a village and looks for the stream that flows through it. It transpires that, after a long period spent in South America, the man is returning to the village in which he grew up. From a bridge, he looks at the stream and it slowly dawns on him that it is flowing the wrong way. Deeply confused, he decides to trace the stream to its source to check if he is right. On his way, he comes to a house in which he sees a woman tied to a chair, forced by a man to drink the blood of a freshly slaughtered lamb. Instinctively, Olivero hurls himself through the open window and rescues her and he and she travel together to the source of the river, which lies at the bottom of a deep pool of water on the moor high above the village. After this bewildering set-up starts one of the most bizarre novels I’ve ever read. Inspired in equal part by Read’s two literary heroes, HG Wells and Joseph Conrad, The Green Child breaks all the rules of conventional fiction and is a real one-off, a true original. You will never read anything like it.

DM Thomas’ The White Hotel

Where Herbert Read’s The Green Child is Jungian, DM Thomas’ The White Hotel is Freudian. Thomas’ book is divided into six parts, the first of which is actually a long, highly erotic, prose poem that we later discover was written on a score for Don Giovanni. The second section is a journal, a prose version of the same events. In the third section, Sigmund Freud introduces his case study of a woman called Frau Anna G, an opera singer who has come to him complaining of pains in her breast and womb. It isn’t until the fourth section, well over halfway through the novel, that we meet the ‘real’ main character—Lisa Erdman—for the first time. In the fifth section, we follow Lisa in the present day as she gets caught up in the deportation of Jews from Kiev in September 1941. The final section is a coda: a kind of dream, or maybe a (death)wish fulfilment—we are never sure what. The oneiric narrative of The White Hotel demonstrates that time is once again treated as an element to be shaped and shifted. The Russian-doll-like structure of the narrative means that we never discover the truth of Lisa Erdman; her character constantly eludes us, just as her own past eluded her.

Dubravka Ugrešić’s The Museum of Unconditional Surrender

This book, which I reviewed for the Financial Times in 1998, was a huge influence on The Red Dancer. Ugrešić’s book is one of the most unusual and original novels I have ever come across: diary entries, footnotes, quotations, descriptions of photographs and bits of autobiography mixed with the cultural history, myth, fables and dreams of her native Croatia—social realism shot through with magic realism. Bears more than a passing resemblance to another great novel of political exile, Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being.

Hugo Wilcken’s Colony

The year is 1928. Sabir—petty criminal, drifter, war veteran—is on a prison ship bound for a notorious penal settlement in the French tropics. On his arrival, he is sent to work camp deep in the South American rain forest. There, he wins the confidence of the camp’s idealistic commandant, who sets him the task of landscaping a lush garden in the wilderness. At the same time, Sabir is planning an escape with a group of fellow inmates, but he realises that his only hope of escape is to become someone else entirely, to slip into a different dream. The novel’s two sections shadow and mirror each other in distorted form; they are internally consistent, and yet not quite consistent when set side by side. The novel travels along a narrative faultline, resisting a totally logical, realist explanation, forcing the reader to look elsewhere for resolution. Think Papillon meets David Lynch’s Lost Highway.

This list appeared as a guest post on Ruby Speechley's blog in October 2017.