'The most interesting aspect for me, composing exclusively with patterns, is that there is not one organizational procedure more advantageous than another, perhaps because no one pattern ever takes precedence over the others. The compositional concentration is solely on which pattern should be reiterated and for how long ...'

'In that sense, my compositions are not 'compositions' at all. One might call them time canvases in which I more or less prime the canvas with an overall hue of music. I have learned that the more one composes or constructs the more one prevents Time Undisturbed from becoming the controlling metaphor of the music.'

Feldman said his idea was not to ‘compose’, but to project sounds into time, free from compositional rhetoric. ‘I find that as the piece gets longer, there has to be less material. That the piece itself, strangely enough, cannot take it. It has nothing to do with my patience … I don’t have an anxiety that I’ve got to stop. But there’s less going into it, so I think the piece dies a natural death. It dies of old age.’

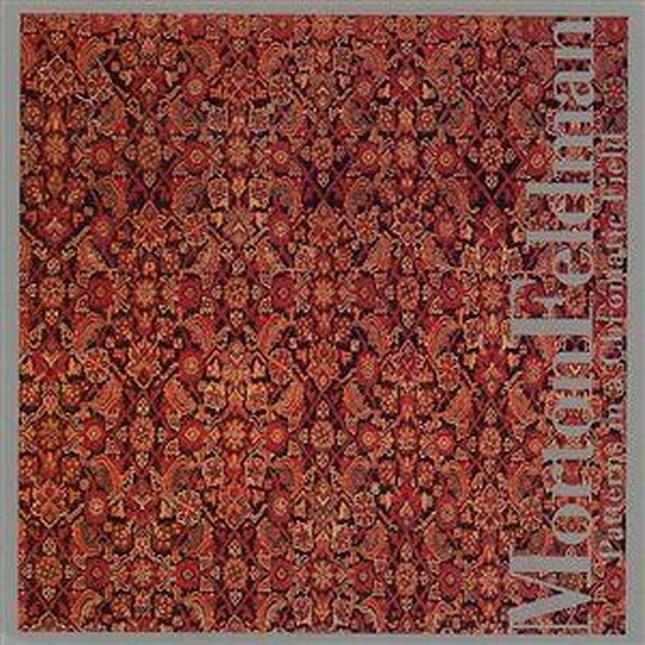

In his ultralong works of the 1980s, Feldman moulded repetition, sonority and memory on a timescale so large as to overpower the listener’s frame of reference. ‘My music sounds like Webern, except longer. But I didn’t get the idea conceptually from music at all. I got the idea from ‘Teppich’ rugs … one of the most interesting things about a beautiful old rug in natural vegetable dyes is that it has ‘abrash’, which is that you dye in small quantities. You cannot dye in big bulks of wool. So it’s the same, yet it’s not the same. It has a kind of micro-tonal hue. So when you look at it, it has that kind of marvellous shimmer which is that slight gradation.’

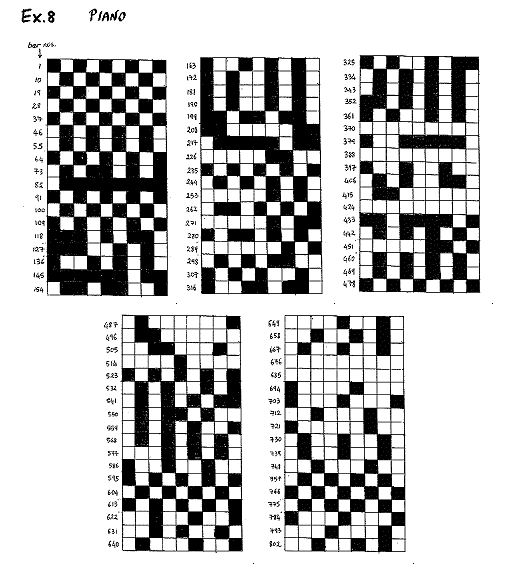

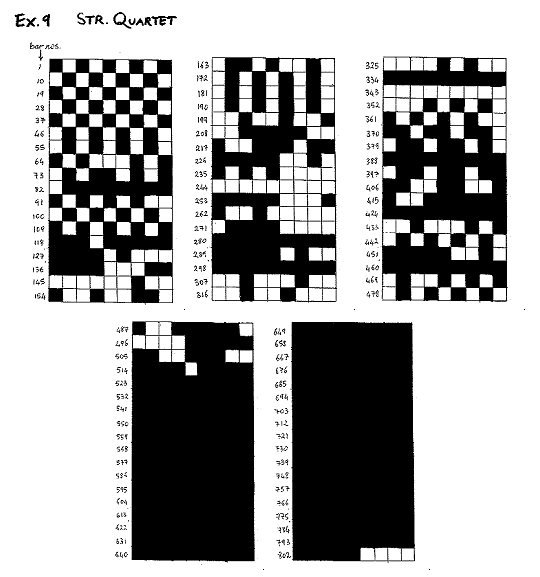

It is impossible not to mention Turkish rugs when writing about Feldman's late music, especially with regard to the visual aspect of his scores. Ex.8 and Ex.9 are visual renditions of the piano and string quartet parts respectively of Piano and string quartet (1985).